-

Triangle galaxy

Triangle galaxy

-

Air conditioning

Air conditioning

-

Coulomb

Coulomb

-

Straight swift

Straight swift

-

Dark energy

Dark energy

-

Saccharose

Saccharose

-

Iron-bearing formation

Iron-bearing formation

-

Oberon

Oberon

-

Gill rakers

Gill rakers

-

Acidosis

Acidosis

-

Viking 2

Viking 2

-

Parenchyma

Parenchyma

-

Krebs cycle

Krebs cycle

-

Homography

Homography

-

Riveting

Riveting

-

Permanent meadow

Permanent meadow

-

Microsoft System Center DPM

Microsoft System Center DPM

-

Lunar month

Lunar month

-

Pink moon

Pink moon

-

Limestone pavement

Limestone pavement

-

Hyakutake's comet

Hyakutake's comet

-

Oncotic pressure

Oncotic pressure

-

Fibrin

Fibrin

-

Debubblizing

Debubblizing

-

Fish-eye

Fish-eye

-

Biomass

Biomass

-

Onco-haematologist

Onco-haematologist

-

Allergy

Allergy

-

Peritoneum

Peritoneum

-

Diagenesis

Diagenesis

Sponge

Sea sponges or simply sponges, both names from the Latin word spongia meaning "sponge", are members of the phylum Porifera. They can be subdivided into three classes: Demospongiae, Hexactinellida and Calcarea. Sponges are organisms classified as sessile metazoans, meaning they are comprised of several cells directly inserted or fixed onto a foreign support. They inhale and exhale through pores connected to a chamber containing the choanocytes, which are cells that have flagella used to bring food towards the animal. Sponges take on the characteristics of diploblastic animals. Their bodies are lifeless masses contained within two embryonic sheets: the ectoderm, which is located on the exterior, and the endoderm, which is located on the interior. Sponges are part of the animal kingdom and do not have a nervous system.

Agelas oroides. © Esculapio, GNU FDL Version 1.2

There are about 9,000 species of sponges, which are currently divided into several groups, such as siliceous sponges and calcareous sponges. Siliceous sponges include Demospongiae, which include bath sponges (Spongia officinalis found in the depths of the Mediterranean) and Hexactinellid sponges, also called glass sponges. Calcareous sponges have a calcium carbonate skeleton.

Clathrina chlatrus. © Elapied, CCA-SA 2.0 France license

Description of sponges

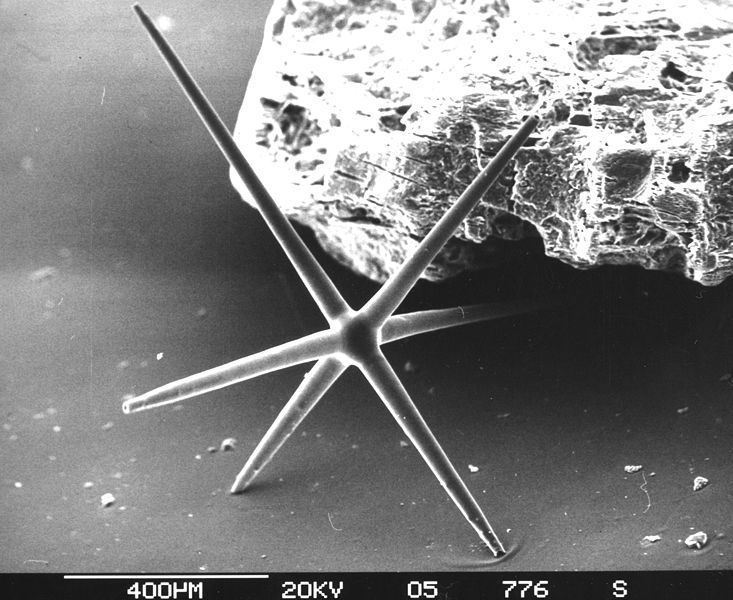

Most of the time, sponges are sedentary organisms. Sponges can be found in creeping form, called encrusted sponges, or arranged in the form of a cup, bowl or branches. These branches are often fan-shaped or decorated with tufts. Their anatomy is designed to facilitate water filtration. Sponges can be found in many colours: yellow, brown, red-violet, blue, as well as white or cream, which may be due to pigments, algae, bacteria or metallic salts. These animals have no respiratory system, no genital system and no excretion system. The skeletal structure of the different groups is characterised by the nature of its calcareous or siliceous spicules, which are extracellular mineral secretions found in tissues. They also contribute to supporting tissues or anchoring the sponge in place.

_2_.jpg)

Cliona viridis. © Parent Géry, public domain

The consistency of a sponge depends on the physical structure of its internal skeleton, which is defined by the type of spicules, their density and their position. Sponges are also characterised by their collagen content. Collagen is a protein that gives the tissues mechanical resistance to stretching. Sponges are also characterised by their spongin content, which is a protein that facilitates the association between the living organic matter and a rigid mineral body. The size of a sponge varies according to its type. The smallest are calcareous sponges, which rarely grow larger than 5 centimetres. The size of Demosponges varies from centimetres to metres, while the span of siliceous sponges can fluctuate from several dozen centimetres to several metres.

Ianthella basta. © Richard Ling from NSW, Australia, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license

Sponge habitat

With a few rare exceptions, sponges are sessile organisms, meaning that they live on different types of supports: hard rock, sediment, crustacean cuticles, shells...They are mainly found in shallow littoral areas (between 6 and 20 metres deep) where they find abundant sources of food, but some species may live in abyssal depths, up to 8,600 metres deep. The group of Hexactinellids displays its widest diversity of forms and colours in the bathyal zone, between 200 and 600 metres deep, while different forms of calcareous sponges are found widespread at depths of less than 100 metres. But this distribution is not set in stone. In fact, in 1998, a carnivorous sponge that was in principal abyssal, Asbestopluma hypogea, was discovered in an underwater grotto near the coast of Provence, at a depth of between 15 and 25 metres. Sponges are also found in fresh water, even in France, such as: Ephydatia fluviatilis or Spongilla lacustris, among others.

Spongilla lacustris. © Kirt L. Onthank, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license

Sponge behaviour

In order to thrive, sponges need to be attached to supportive surfaces, and they take on their specific shapes according to what kind of supportive surface they are attached to. Other rarer species float, such as Suberites carnosus, which is orange in colour and simply places itself at the bottom of the water, on the sand, and lets itself drift along . The ecological role of sponges is important, for they provide shelter to many species of commensal animals, which take advantage of the food contributions their hosts provide, such as shrimp from the genus Euplectella or the larva of some fresh water insects. There are also so-called mutualist associations, in which sponges attach themselves to the shell of a crustacean. This crustacean is then protected by the sponge, which does not have any predators, while it benefits from the leftovers of its meals. Some sponges practice parasitism by attaching themselves to the shells of molluscs that they pierce by dissolving it. They are also the only animals known to live in symbiosis with cyanobacteria.

Haliclona permollis. © jkirkhart35, CCA 2.0 Generic license

Sponge diet

Sponges essentially consume bacteria, organic debris and unicellular algae. Organic and inorganic particles suspended in the water are inhaled through the pores. Organic particles are digested, while inorganic particles, such as grains of sand, are expelled through the pores during exhalation. The carnivorous sponge discovered in the Mediterranean in 1998 is able to capture and digest prey, even though it does not have a digestive cavity.

Cliona celata. © Matthieu Sontag, GNU FDL Version 1.2

Read or review

The file on carnivorous sponges.

A sponge spicule seen through an electronic microscope © Hannes Grobe/AWI, Wikimédia CC by 3.0

A sponge spicule seen through an electronic microscope © Hannes Grobe/AWI, Wikimédia CC by 3.0

Latest

Fill out my online form.